|

|

CINERAMA:

The Last Belch

None

of us went to see How the West Was Won

for history, we went for the ride. The

second and last of the three-strip Cinerama “story” roadshows was

expressly designed to use the medium to its fullest: the charging Indians

on the warpath, the roaring choo-choo and the timber about to tumble from one of its cars, raft cascading down the rapids, buffalo on a rampage and the

nearly endless stunts are for no other purpose than swooning over the whirling

imagery and vibrating to the thunderous sound. The younger or more

impressionable the viewer during the initial run, the more successful the

movie was deemed. (You understand why director Ron Howard as a kid was so

impacted and clearly see the process’s influence in his Far and

Away.) For adults, however, there’s considerable frustration. It’s

a sprawling hodge-podge of episodic and generational vistas failing to flow to

or from each other with ease. Meaningful narrative connection is missing,

regardless of Spencer Tracy’s vocal annotations

reminiscent of De Mille, and we’re feeling undernourished; between wowie

effects, we get table scraps of history, humor and concession stand drama.

The Civil War sequence, directed by John Ford, is starving for clear-headed

detail—we can’t really tell where we are or why we’re there, other than

for John Wayne to listen to Henry (Harry) Morgan as Grant worrying about

the gossip the newspapers are printing about him as a drunk and for

George Peppard to prevent Morgan from being assassinated by Russ Tamblyn.

Unaccountable why dullard

Peppard is basically the star of the second half of the movie. (Hope Lange as his love interest was mercifully edited out.) The cast is

early 1960s billboard glory—Debbie Reynolds, James Stewart, Gregory Peck,

Henry Fonda, Richard Widmark, Robert Preston, Carroll Baker, Thelma Ritter

and fifteen other recognizable names—but the acting isn’t. Though

reluctantly accepting Baker’s almost touchingly

funny quest for Stewart, who’s made out to be a babe magnet which

should send us all packing, and concede to Reynolds for trying to escape the very stiiff confines demanded by the Cinerama camera(s), the least constricted performing in the entire movie is when Peppard’s dog, who doesn’t

have the dreaded doggie stare looking for instructions from his trainer, walks away on a porch. Its genesis from a photo essay published in Life, James R. Webb’s screenplay won an Oscar, and to this day no one can figure out why. But the Academy voters clearly rewarded Harold F. Kress for his long months of labor in trying to edit the contraption. MGM’s voting block got the epic nominated for best film,

color art direction, cinematography, costume, sound, original musical score.

This last nom a real insult to lovers of movie music: listening to Dave Guard

and the Whiskeyhill Singers and the Ken Darby Singers is like one long cringefest. The non-war

segments are directed by George Marshall and Henry Hathaway. People

knowledgeable about the difficulties with Cinerama swear the real directors

were photographers Williams H. Daniels, Milton Krasner, Charles Lang, Jr.

and Joseph LaShelle. After the Cinerama runs, How the West Was Won was released in both 35mm and Ultra Panavision prints. (Opening 2/27/1963 at the McVickers, running 37 weeks.)

Using

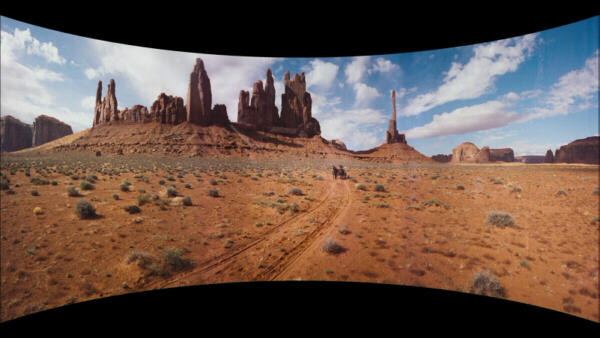

Smilebox and other corrective technology via Blu-ray,

How the West Was Won is the best restoration of a mediocre

movie I’ve seen before the Blu-ray of Doctor Zhivago. Simulating the curved Cinerama screen effect, the movie

finally becomes substantially more watchable. The original Cinerama

movies have always been problematic for audiences because of those damned

two seams joining the three camera technique; even with all the

camouflage (trees, mountains, poles, buildings, overstuffed sets, etc.) used

to conceal, the seams were persistent distractions. If the prints were old

and dirty, the color differences and scratches in the strips were additional

annoyances, as were projector misalignments. And of course, the blocking of actors so exaggerated

as to become exhausting to watch: the performers

were too often anxiously crammed into the middle panel to help avoid the

distortions of movements occurring as they moved into the views of the left and/or right panels.

When the actors were speaking to each other, they often didn’t look like

they were looking at one another because in fact they weren’t, hoping to compensate

for the huge 146 degree expanse of screen angle and only occasionally did

the trick work. Cinerama was great for outdoor panoramas and action, especially

if the three cameras were moving straight forward or if the action moved

towards the audience. But when the buffalos were

moving from one side to the middle and then to the third side, the distortion was peculiarly zigzaggy,

without logic to the eye. The process took in busied up large sets with high

satisfaction; sets of a reduced size, like a train car or

a hotel bedroom, went warpy by the camera angles suggesting an

accidental example of some of Terry Gilliams’s Mad Hatter designs. Processed

shots—in-studio action on rafts and railroad

cars—were and remain pitifully exposed. With only a few original 3 panel Cinerama theatres left, the closest an audience can get to the promise of what the process offered—mainly screen size and the flawed sense of depth—are the violative 35 and 70mm transfer prints on the box. This changes dramatically with the 2008 release

of Warner Bros. Blu-ray edition of the restoration:

HWWW is a

“must see” curiosity for lovers of Cinerama and those new to it.

The enhancements of color, definition, sound, sound

effects and the Smilebox simulaton of depth make it a breaktaking improvement over the original. The biggest and most obvious

betterment is the near elimination of those two lines. Some are still present, in the unnecessary lifts from The Alamo and Raintree County as glaring examples.

The crystal-clear imagery and its cleanliness help us get past the cliche-ridden story; the daytime sweeps provide us with

the sensation of textures, as we can virtually reach out and touch the lumber,

trees and most amazingly the dirt of earth. The night scenes, including

those for the Civil War, have

a near-transcendent spell about them; we get caught up in an allure of luxury.

The restoration isn’t confined to

Cinerama. The technicians provide a flat-screen version with all the improvements, sans Smilebox’s curvature, and it’s the one TCM now airs.

The deluxe Blu-ray packaging includes the Random House hardcover souvenir booklet (with a better cover shot), the flat-screen version and the fun and informative documentary Cinerama Adventure. Since 2008, the Cinerama travelogues have been restored twice, utilizing advances in corrective software, and it’s expected but not confirmed HWWW will also undergo a second refurb. Using

Smilebox and other corrective technology via Blu-ray,

How the West Was Won is the best restoration of a mediocre

movie I’ve seen before the Blu-ray of Doctor Zhivago. Simulating the curved Cinerama screen effect, the movie

finally becomes substantially more watchable. The original Cinerama

movies have always been problematic for audiences because of those damned

two seams joining the three camera technique; even with all the

camouflage (trees, mountains, poles, buildings, overstuffed sets, etc.) used

to conceal, the seams were persistent distractions. If the prints were old

and dirty, the color differences and scratches in the strips were additional

annoyances, as were projector misalignments. And of course, the blocking of actors so exaggerated

as to become exhausting to watch: the performers

were too often anxiously crammed into the middle panel to help avoid the

distortions of movements occurring as they moved into the views of the left and/or right panels.

When the actors were speaking to each other, they often didn’t look like

they were looking at one another because in fact they weren’t, hoping to compensate

for the huge 146 degree expanse of screen angle and only occasionally did

the trick work. Cinerama was great for outdoor panoramas and action, especially

if the three cameras were moving straight forward or if the action moved

towards the audience. But when the buffalos were

moving from one side to the middle and then to the third side, the distortion was peculiarly zigzaggy,

without logic to the eye. The process took in busied up large sets with high

satisfaction; sets of a reduced size, like a train car or

a hotel bedroom, went warpy by the camera angles suggesting an

accidental example of some of Terry Gilliams’s Mad Hatter designs. Processed

shots—in-studio action on rafts and railroad

cars—were and remain pitifully exposed. With only a few original 3 panel Cinerama theatres left, the closest an audience can get to the promise of what the process offered—mainly screen size and the flawed sense of depth—are the violative 35 and 70mm transfer prints on the box. This changes dramatically with the 2008 release

of Warner Bros. Blu-ray edition of the restoration:

HWWW is a

“must see” curiosity for lovers of Cinerama and those new to it.

The enhancements of color, definition, sound, sound

effects and the Smilebox simulaton of depth make it a breaktaking improvement over the original. The biggest and most obvious

betterment is the near elimination of those two lines. Some are still present, in the unnecessary lifts from The Alamo and Raintree County as glaring examples.

The crystal-clear imagery and its cleanliness help us get past the cliche-ridden story; the daytime sweeps provide us with

the sensation of textures, as we can virtually reach out and touch the lumber,

trees and most amazingly the dirt of earth. The night scenes, including

those for the Civil War, have

a near-transcendent spell about them; we get caught up in an allure of luxury.

The restoration isn’t confined to

Cinerama. The technicians provide a flat-screen version with all the improvements, sans Smilebox’s curvature, and it’s the one TCM now airs.

The deluxe Blu-ray packaging includes the Random House hardcover souvenir booklet (with a better cover shot), the flat-screen version and the fun and informative documentary Cinerama Adventure. Since 2008, the Cinerama travelogues have been restored twice, utilizing advances in corrective software, and it’s expected but not confirmed HWWW will also undergo a second refurb.

ROLL OVER IMAGES

(from the SmileBox Edition)

Go to Top of

Page

ralphbenner@nowreviewing.com

Text COPYRIGHT © 2002 RALPH BENNER (Revised

2018.) All Rights Reserved. |

![]()

![]()